Hastings – St Mary-in-the-Castle (old and new)

There have been two churches. First was a mainly collegiate one within what became the castle, though it is probably older. This survives as a ruin, the structure of which is C11, though altered in the C12 and C13. A new church with the sane dedication on the sea front was built in 1825-28 on an unusual semi-circular plan.

Old Church

Hastings castle was built after the Conquest on a hill where a church already stood. The college of priests present in the C13 claimed Edward the Confessor as their founder (VCH 2 p112) and the architectural evidence confirms that the oldest parts predate the castle, though more probably it was first intended as a minster. Robert, Count of Eu, builder of the castle, may have founded the college in 1090. Precise evidence is lacking, though Levien found references by 1093-94 (3 p124). The castle passed to the king in 1215 and in 1267 the church became royal and thus free from episcopal supervision (VCH 2 p117). However, in 1460 the bishop of Chichester acquired jurisdiction, reflecting the decline of the castle, which had failed to impede the French raids. This was possibly because erosion had already diminished its usefulness; its south side has now vanished entirely. The college was dissolved in 1547, but as the church was also parochial, services continued until the late C16 under the auspices of the vicars of St Clement and All Saints (2 p174). Thereafter it was ruinous and disused, though a civil parish survived. In 1601 the lordship of Hastings, including authority over the castle, passed to the Pelhams (VCH 9 p3), but this made no difference to the church.

The ruins are mostly of sandstone and show how an axial-tower plan evolved into one which had one and possibly two west towers and a south chapel. The oldest part of an irregularly laid out church is the central tower, which has herringbone masonry and is likely to be C11. Taylor (III p1073) suggested that it might originally have formed the chancel and identified pre-Conquest work in the rounded stair-turret to the north. The north wall of the nave is well preserved, as it was subsequently incorporated in the curtain wall of the castle. Despite later repairs, there is a visible join with the later western part. Inside are traces of C11 round-headed wall-arcading and stone seats; to the south the only substantial walling is towards the east, showing the outline of a round-headed niche. Up three steps to the south of the tower is a transept-chapel with a small projecting rounded eastern altar-recess. The herringbone masonry and well preserved internal quoins also look C11. A round-headed west arch led into a cloister or aisle, and there is a doorway of uncertain date with a square lintel.

Near the west end to the south, the join in the north wall is matched by what seems to have been an internal buttress. The western part of the nave may have been added in the late C12, the date of the squat north west tower with a plain round-headed west window high up and the jamb of a larger south opening. It could have been part of the defences, though, less plausibly, it has been suggested that it was one of two west towers of the church (1 p135) joined by a lower narthex, though no trace of a south one has been found. Two doorways in the nave opened onto an outer passage or gallery.

Soon afterwards, a chancel was added east of the central tower or, if there was a previous one, rebuilt. As part of this, an early C13 arch, now weathered, was inserted in the west side of the tower. Its has square responds with corner shafts bearing foliage capitals and a head of two keeled and moulded orders, the inner on foliage corbels. The chancel is at an angle to the tower and its small size suggests the college would still have had to use the nave. Though the walls are C13, nothing recognisable remains. Of the three small chambers to the north, a rib-vaulted one was perhaps a sacristy. A blocked roll-moulded and pointed east window show it was also C13.

After it fell into ruin, little was done to the church before repairs in 1824 to the castle generally. The C13 arch in the tower was rebuilt using the old stones and the north wall of the nave was repaired with the curtain wall of which it is part.

New Church

The repairs to the castle in 1824 reflected an increasing interest in the picturesque. In 1825, the land along the shore below the castle hill was developed as part of the resort by the Earl of Chichester who owned it. At its centre was Pelham Crescent, so called after the family’s surname. The architect, J Kay (Colvin 4th ed p600), was experienced in the laying out of new residential developments and had worked for the earls at their seat at Stanmer (4 p93). At Pelham Crescent he placed a proprietary chapel at the centre with a curved terrace of houses each side. These have canopied balconies and distinctive semi-circular attic windows. The chapel was named after the church in the castle, which presented no problem, as the earl owned that too.

Though the chapel was complete by 1828, the houses on the western side were still unbuilt in 1836 (ESRO Par 369/4/2/1). The crescent and in particular the chapel are built against the hill, so only the facades facing the sea are visible. They are approached up a series of ramps, which Richard Morrice suggests derives from the Roman temple of Fortuna Primagenia at Palestrina, south of Rome (4 p111). Kay had access to more than one reconstruction of this. Under the chapel were burial vaults. The front of the church, though classical, is less obviously Roman. Above a pedimented Ionic portico, flanked by big windows, is the flat front of the upper part and behind the portico a deep recess containing two more pillars.

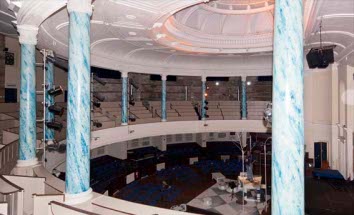

The interior is shaped like a D, with a domed roof and galleries round the curved side, which are supported on iron piers that are encased in wood. They are painted in imitation of marble of a curious blue hue that can have had few models in nature and the effect is very much like a theatre of the period. Along the straight wall behind the portico is an altar recess, which thus actually faces south. Ironwork is also to be found in the roof, which gave problems within a year of completion (5 p61). The only direct light comes through a lantern in the centre of the roof, surrounded by a band of acanthus leaves, so the overall effect recalls a theatre. As built, the altar recess was flanked by a pulpit and reading desk. Behind a curved altar rail stood the font (Yates p106).

The plan is a late example of the auditory church taken to extremes and was intended to bring the congregation into closer proximity with the preacher, whilst avoiding any display of religious emotion. Earlier examples of churches avoiding the customary rectangular plan, such as St Chad, Shrewsbury (1790-92) had been round or octagonal (see W Whyte p46 for a fuller discussion of the issue).

The church became parochial in 1884 (CBg 51 p60) and was altered in 1888-89, as an inscription records, though the name of the architect on that occasion is not known. Short of complete rebuilding, the plan and the style could not be changed, but the entrances to the sides of the altar recess may have been altered and the recess was refitted and decorated (see below). In 1938-39 there were repairs to the roof by H M Jeffery (ICBS). The later history has not been happy. Merged with Emmanuel church in 1953, it ceased to be used in 1970 and was sold to a nonconformist congregation, which found itself unable to maintain the building. After various abortive plans whilst the structure decayed further, in 1990 the Council acquired it. Repairs were instituted under Adams Johns Kennard (CBg 18 p65), even before the future use of the building had been decided. Eventually it was turned into an arts centre and work was completed around 1998. The galleries were kept, but not the pews at ground level. The organisation that took on the running of the arts centre ran into financial difficulties and was followed by two short-term replacements. At the end of 2012 the Council approved plans by Buckswood School, Guestling which would continue the use of the building for cultural purposes and by 2017 it was in regular use for such purposes.

Fittings

(Before conversion)

Decoration: (Altar recess) 1893 by H Weston and H Tickner (BE p521) in rather sombre colours, now rather scuffed. This work incorporates part at least of the original reredos, particularly the boards bearing the Creed etc since the style of lettering was no longer used after about 1840.

Font: This is unusual in an Anglican church as it is a tank for baptism by immersion. It dates from 1928 and is fed by one of the five springs found emerging from the cliff-face when the church was built (5 p60).

Glass:

1. (centre east (actually south) window) Heaton, Butler and Bayne, 1921(www.stainedglassrecords.org retrieved on 5/3/2013). A large composition with the Angel announcing the Resurrection.

2. (Baptistery) Glass panel, P W Cole, 1934 (ibid, retrieved on 16/2/2015)

Sources

1. F H Baring: Hastings Castle (1050-1100) and the Chapel of St Mary, SAC 57 (1915) pp119-35

2. A Boulter-Cooke: The Twin Churches of St Mary-in-the-Castle, Hastings, SCM 18 (July 1944) pp174-76

3. E Levien: History of St Mary’s Collegiate Church in Hastings Castle, JBAA 23 (1868) pp124-34

4. R Morrice: Palestrina in Hastings, GGJ 11 (2001) pp95-115

5. A Stocker: The Church of St Mary in the Castle, Hastings, CBg 56 (1998) pp60-63

6. E Turner: College and Priory of Hastings, SAC 13 (1861) pp132-79

Plan of old church

Plan of castle showing church in VCH 9 p16

My thanks to Nick Wiseman for the photographs of both churches