Easebourne – St Mary

A C11 church was extended around 1200 and a parallel nave was added in the mid-C13, when it became the church of a nunnery, parts of which still stand. There was a drastic restoration in 1876-77.

Easebourne gave its name to the hundred in which it lies and the church may have been a minster (VCH 4 p53). The post-Conquest market town of Midhurst, of which it is now effectively part, was originally a chapelry in the parish. The church at Easebourne existed by 1105, when it was given to the Norman abbey of Sées (2 p8), but around 1216 a college of priests was established. This served not only Midhurst but other chapels such as Fernhurst and Lodsworth (6 p113). Around 1240 this was transferred to the Benedictine nuns of Rusper (by Horsham) (ibid p115) and became a subsidiary house, probably because it was poorly endowed (2 p9). It remained so until it was dissolved in 1536, though by 1438 it had become, under circumstances that are unclear, a house of Augustinian Canonesses. The various occupants during this period used and extended the church.

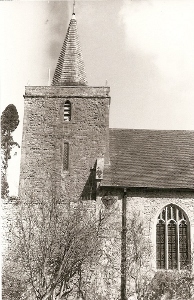

The church today has two naves; that to the south is the original, for its south wall, normally inaccessible today, is C11, as some repointed herringbone masonry and a tall, narrow round-headed doorway (blocked) show. The doorway, despite its proportions, is post-Conquest. A north aisle and tower were added a little before 1200, as the style might suggest, or possibly following the foundation of the college of priests. The aisle no doubt had a lean-to roof, though nothing remains except for some of the west wall, beneath C19 refacing, and one and a half bays of a three-bay arcade. Its broad double-chamfered arches are pointed and the octagonal pier has a scallop-capital. On the west respond is a corbel beneath more scallops for the inner order of the arch. The unbuttressed tower, though altered, keeps its original small openings; the lower ones round-headed and the rest pointed, like the plain chamfered tower arch and the west doorway.

Presumably after the nuns came, they obtained sole possession of the eastern part of the formerly parochial south nave after they had replaced the lean-to north aisle by a parallel nave, into which the parish was moved. The newly acquired south eastern nave became the nuns’ choir and to ensure separation they replaced the east bay and a half of the arcade by a wall; the western bay and a half remained open and the western part of the south nave was parochial. The arrangement of parallel naves is less usual in churches shared by a religious house and a parish than that exemplified by Boxgrove, where the parish used the nave and the chancel was monastic. At Easebourne the parochial nave is gabled and as wide as the original one. The Burrell Collection drawing and Adelaide Tracy (I p113) show it had lancets, of which one rere-arch with a scoinson (dating it well into the C13) survives. The nuns also rebuilt the chancel to the east of the southern nave, so that it became possibly twice as long as now, with a square east end (5 p99). To its north stood a parish chancel, which may be the low east extension shown by Quartermain ((W) p93) in this position, on which there is no further information.

Little more than windows were altered during the later Middle Ages. The south side abutted onto the cloister and thus the only windows were high up. The Burrell drawing shows a four-light square-headed one, which looks C15 like the panelled tracery of the former west window of the parish nave, which is shown by Adelaide Tracy. This was moved in the C19 to the south side (BAL MSS/DB 6/3/1) and keeps its old head. The retooled moulded western arch of the nuns’ choir with semi-octagonal respond could date from the C15, but could equally be connected with a bequest by Sir David Owen in 1529/30 (see under monuments below) for alterations to the nuns’ choir, the purpose of which was to allow them to enter unseen from the convent (SRS 42 p100), though it is hard to see how such a broad arch could have helped this.

After the dissolution, the nuns’ choir and chancel were unroofed (2 p9), though by the C18 the nuns’ chancel had become a funerary chapel for the Montagues of Cowdray (4 p6). It remained roofless until E Blore (Colvin 4th ed p133) rebuilt it in shortened form in 1834-36. The parish chancel shown by Quartermain could date from then. At some time, under-sized pinnacles were placed on the tower.

The present appearance of the church is due to Sir A W Blomfield‘s restoration in 1876-77. The specification of work (BAL MSS ibid) reveals that he virtually rebuilt the north nave and chancel with lancets, restored the arcade to three bays and replaced the south windows. All roofs were renewed (much of the south nave had previously been roofless (2 p10)) whilst Blore’s south chapel was remodelled with a new east window with three plain lights. The north chancel has much arcading and shafting and is entered through a new chancel arch. A plan to heighten the tower with a taller spire was dropped, though the present one differs from the shingled one in the Sharpe Collection drawing (1804). Finally, Blomfield refaced almost everything except the north and west sides in unattractive, rough stone. Sir A Webb refaced the north side in 1912, at the expense of Lord Cowdray (4 p15) for whom Webb did work at Cowdray Park (BE(W) p348), but his work differs hardly from Blomfield’s. A plan to extend the chancel and to treat the west end similarly was frustrated, presumably by World War I. There were repairs by S Roth in 1952-53 (ICBS).

Fittings and monuments

Font: The usual C12 square bowl, arcaded on three sides and with renewed shafts.

Glass:

1. (East window) Heaton, Butler and Bayne, 1877 (CDK 1880 pt2 p121).

2. (North chancel) Heaton, Butler and Bayne, 1879 (www.stainedglassrecords.org retrieved on 11/2/2013).

3. (North nave, first window) H T Bosdet, 1894 (signed). The naturalistic foliage at the base of the figure is beautifully observed.

4. (North nave, west window and roundel) Heaton, Butler and Bayne, 1877 (ibid).

5. (South side, second lancet) R Sprey, 2000 (adjacent notice). A Millennium window.

Monuments:

1. (North nave in reset C13 cusped recess) Sir David Owen (d1535). He was the owner of Cowdray, a natural son of Owen Tudor and thus uncle to Henry VII (Visitation of 1530 etc p94). His armoured alabaster effigy is conservative for the date of death. In fact, it was made long before, for in his will of 1529 Owen directed it should be re-gilded (1 p33). Originally there is said to have been also an effigy of his wife (ibid).

2. (South chancel) Sir Anthony Browne, later First Viscount Montague (d1592), attributed to G Johnson (A White (WS 61) p68). The Brownes bought Cowdray from Owen. This monument was originally in Midhurst church and free-standing, but was brought here in 1851. As there was less room, it was re-arranged, with Lord Montague kneeling behind and above the two recumbent effigies of his wives, instead of having a wife on either side (4 p14), with obelisks at the corners. The original arrangement resembled Johnson’s monument to the Earls of Southampton at Titchfield, Hampshire (A White p65), unsurprisingly perhaps as Montague’s daughter was married to Henry, Earl of Southampton (Visitation of 1530 etc, p84).

3. Elizabeth Poyntz (d1830) A seated female figure by Sir F Chantrey. It was ordered in 1832 (M Brown p272), so Gunnis’s suggestion (p95 – not repeated in Roscoe) that it was possibly made in 1814 is erroneous. She was the last surviving Montague.

4. William Poyntz (d1840) Her husband, by the Italian R Monti. It was made in 1848 (Roscoe p840 as ‘Eastbourne’) and the identical surround in gothic style shows it was deliberately intended to match his wife’s monument.

Reredos: Stone with marble shafting, showing the Last Supper. It would be tempting to ascribe it to Blomfield, but the date of 1899 has been suggested (BE(W) ibid) .

Conventual buildings

[NB. the house and its garden on the site of the cloister are private and normally inaccessible]

The conventual buildings lay around a cloister south of the church. The east range, later adapted as a house, is at right-angles to the chancel. Though the nuns did not have their own church, their buildings were impressive, to judge from what is left. The west front of the main house incorporates a triple chapter house entrance of c1270 with moulded arches and complex piers incorporating marble shafts. Despite restoration – the marble shafts are renewed and the Burrell drawing shows the openings blocked – the quality is higher than anything in the church. South of this a round-headed arch leads to a passage. The upper storey containing the dorter was renovated in the C15 with one- and two-light square-headed windows. Along the south walk of the cloister is the refectory, which has early C14 south windows of Y-tracery, now renewed. There were almost certainly originally four not three, since the Burrell drawing shows a large opening with double doors where the long gap between the second and third windows now is. The structure was later used as a barn (Hussey p223), for which the opening was made, and today is a parish room. Only a wall marks the position of the west range.

Sources

1. W H Blaaw: The Effigy of Sir David Owen in Easebourne Church, SAC 7 (1854) pp22-43

2. A Bone: Easebourne: St Mary’s Church and Priory, NFSHCT 2012 pp8-11

3. W H Godfrey: Parish Church (and Priory) of St Mary’s, Easebourne, SNQ 13 (May 1952) pp209-12

4. H Hinkley: Easebourne. Its Church and Priory, Revised 1977 by M C Field

5. W H St John Hope: Cowdray and Easebourne Priory, London 1919

6. N Vincent: A Nuns’ Priests’ Tale: the Foundation of Easebourne Priory (1216-40), SAC 147 (2009) pp111-23

Plan

Measured plan of church and priory by W H Godfrey in VCH 4 p48

My thanks to:

1. Richard Standing for the photographs identified ‘RS’ in the titles

2. Nick Wiseman for the photographs identified by ‘NW’