Boxgrove – St Mary and St Blaise

The present church is that of a former priory, founded after the church was acquired by the Norman abbey of Lessay in 1105. The transepts and the nave (now ruined) were substantially complete by possibly as early as c1170. The choir was rebuilt from the 1190s in a style close to Chichester cathedral. Later changes consisted of windows, a C14 porch and a C15 vestry. The De la Warr chantry of c1530 survives.

A church at Boxgrove is mentioned in Domesday Book (II, 2), when it had several clerks, which suggests it was a minster. In 1105 the advowson passed to the Norman abbey of Lessay (VCH 4 p149), which probably shortly afterwards established a daughter house here. The dedication to St Blaise, patron saint of wool-combers and weavers (Jessup p79), recalls that its prime importance was economic, as it provided a source of income, mostly from wool, which was then England’s main export. Lessay had other estates in England, which were managed from here. Unlike most alien priories, Boxgrove was quite large by the late C14, when it secured its independence (VCH 2 p57), so it was not dissolved by Henry V as an alien priory and lasted until 1537. The parish used the nave and after the dissolution, it moved, unusually, into the monastic choir because of the presence of the de la Warr chantry (see below). It was barely finished and Lord de la Warr petitioned the King to save the choir because of it (VCH 2 ibid).

Nothing of any earlier structure survives above ground, but it has recently been established that at least the eastern part of the originally parochial nave is built on earlier foundations (6 p10), which are likely to belong to the church mentioned in Domesday Book. It is however unlikely that this earlier church would have covered the entire nave as it was extended later.

Churches were usually built from east to west. At Boxgrove, the choir has been rebuilt, so in the case of the earlier church this cannot be proved, though the arches from the transepts into the present choir aisles dating from the 1120s, are a fair indicator. Like the one from the south nave aisle into the transept, they have plain round heads, square responds and moulded abaci. Petit thought these arches could have led to chapels (5 p2), but there seems little doubt that the previous choir had lean-to aisles, for the original roofline of the north aisle can still be made out on the east side of the arch from the transept. Though altered later, the transepts belonged to the first work, as the the round-headed windows, one blocked, and a corbel-table to the south show. There are no north windows as the conventual buildings adjoined the transept, on the wall of which- their roofline can be seen.

The nave is in two parts; the first two bays from the east, which belonged to the monastic church and 10 further bays for the parish. Only the two eastern bays are now roofed, presumably because as part of the monastic church, they were transferred to the parish in 1537. The easternmost bay of the south arcade has a round-headed arch with two slightly chamfered orders and a round pier on a high spurred base and has been dated as early as c1130-40 (www.crsbi.ac.uk retrieved on 1/4/2013). The upper parts were remodelled in the C13 when a vault was added. On the north side there is no arcade, because of the older cloister behind. Its position suggests that any earlier nave was aisleless. The two bays were completed to their full height and probably originally had a wooden roof like the transepts (renewed in the C19). This contrasts with the simple groined vault of the much narrower south aisle. Below the C13 clerestory openings are the outlines of the original ones.

There are differing views over the date of the parochial part of the nave. Most earlier authorities have suggested that it was probably started about 1170, following essentially the design set by the monastic part, though with some modifications. However, Peter Draper (p118) has suggested that it may have been substantially complete by this date. There is a question over the extent to which this applies to the upper parts, for the clerestory lancets were shafted inside, a feature more to be expected at the end of the C12, and a section of the vaulting ribs with dogtooth looks to be of the same date. If correct, this part of the work was probably done at the same time as the vault and other alterations in the two eastern bays.

The parochial nave had a north aisle in the five western bays and further east there is blank arcading like the south arcade, but only half of one double-bay to the north now stands to the height of the former vault and there is only one arch to the south. The arcades have double bays, separated by cruciform piers with angle shafts (mostly missing) and foliage capitals. The round centre piers have scallop-capitals. The pointed arches have two orders, neither of them chamfered. Triple shafts between each double bay suggest a vault was intended from the start over this part of the nave, with each bay of the vault covering two of the arcade. Little remains of either aisle, but at the east end there is clear evidence that they had simple rib vaults.

Before the completion of the nave, the crossing and tower were started. They probably had no predecessors, for such parts were often left unbuilt until more urgently needed parts were completed. This is all the more likely at Boxgrove, since it is unlikely that the crossing would have been replaced within half a century of completion unless there had been a collapse or a fire, which would surely have left other traces.

The present crossing is wholly late C12 and the piers have three large keeled shafts with smaller plain ones by the walls. As in the western nave, the capitals are scalloped, with fretted ends, terminating in what is almost an ogee long before its invention. Similarities between the capitals and work in the Lady Chapel at Chichester (started before the fire of 1187) have been noted (BE(W) p165-66). The mouldings of the arches are complex with head-stops on the labels. Inside, the open tower has four pointed arches each side, divided into pairs by larger double shafts on corbels. The round-headed external openings were by the late C12 an archaism, with deep mouldings and angle shafts. The corners of the tower also have shafts with foliage capitals. Some capitals on the interior openings are earlier in form, including an early C12 one with volutes. It is less likely that these were re-used, as has been suggested (BE p115), than that they were carved well before use. The round-headed lancets of the south transept gable may suggest that it too was altered or completed in the late C12. The top of the tower has heavy battlements which may date from after lightning damage in 1674 (BE(W) p166), as may the low pyramid spire.

The crossing, especially the tower, was probably not complete when work started on replacing the choir. Its predecessor would have been shorter and a new eastern bay was probably built before any demolition was needed. Draper suggests that this was under way in the 1190s, again significantly earlier than has been proposed previously. He bases his argument on the starting date of the chancel of St Thomas-à-Becket, Portsmouth (now the cathedral), which is closely related. This is known to have been started around 1185 and was substantially complete by 1196. It is in a number of respects less developed than the work at Boxgrove, which is likely to be later than the work on the retro-choir at Chichester cathedral to which it is also closely related. That was started after the fire of 1187 and is noticeably more generous than Portsmouth in its use of polished Purbeck marble, including free-standing shafts. Draper suggests that the device of big round arches containing two smaller pointed ones, common to all three, is more likely at Boxgrove if work started in the 1190s and not in the early C13. It is likely that Boxgrove choir is the work of Chichester masons, who were less constrained than at the cathedral where there was a need to follow the proportions of the retained parts of c1100 further west, as shown by the awkwardly proportioned triforium there. It is, however, conceivable that there was an earlier source for the double bay design, which could have originated at the parent of Portsmouth church, the vanished Southwick priory (Hampshire). Re-founded in c1145, this was probably still under construction in the late C12.

The choir is higher than the nave and as the east crossing arch was not altered, this is markedly lower than the vault. Though it is divided into four bays by flying buttresses, there is little emphasis on the verticals, following English rather than Norman-French taste, and this makes the young Sir Stephen Glynne’s admiration in 1826 of its ‘great loftiness’ surprising (SRS 101 p43). No change in construction is apparent outside, despite being built over an extended period from west to east. Each bay of the aisles had two lancets, with a string-course linking the heads of the tall lancets in the clerestory, beneath a prominent corbel-table. These add further horizontal emphasis. Even at the east end, the verticals are offset by string-courses separating the gable from the triplet of lancets and between their heads; the latter continues each side to the angle-buttresses, which are decorated with dogtooth and head-stops (renewed).

The galletted flintwork of the exterior differs from the older parts, though the galletting may result from later repairs. Inside, the arcade design evolves from the east end, becoming simpler with less dark marble. Unlike New Shoreham, where the changes in design seem to be without purpose, the overall bay design does not vary and copes with the changes. The two-in-one arrangement is already to be found in the western nave, but here, following Portsmouth and Chichester, there are two moulded and pointed arches in a large round-headed one, similarly moulded, with head-stops on the label. The spandrels above the two pointed arches contain a deeply incised quatrefoil, another feature related to the triforium of the retro-choir at Chichester and the arcades at Portsmouth.

The piers show most variation (in this description ‘main pier’ means the pier between the round-headed arches; ‘centre pier’ the smaller ones within each double bay). Starting from the east, the respond and the first main pier have clustered alternating stone and marble shafts and the first centre pier has four free-standing marble shafts round a larger central one. All marble capitals are simple and bell-shaped. The second main north bay is similar (the south one was altered to house the de la Warr chantry (see below)). The freestanding shafts resemble those in Chichester retro-choir. There may then have been a pause, perhaps for the old choir to be removed, for the third bay is different; the round centre piers have no shafts, though still of marble. The fourth main piers and west responds are stone and octagonal, with marble only on the abaci. Oddly, this latest design of pier most recalls those at Portsmouth, though this may be chance. In the fourth main bay the centre pier is similar but smaller. A possible reason for the plainer octagonal piers is that they were largely concealed by the monks’ choir-stalls, which probably stood here (TP). All the centre piers have single leaves above the abaci.

A string-course separates the arcades and the clerestory, which has a wall passage and is identical throughout. As outside, the horizontals are emphasised. The dark abaci, the string-courses and the broad arches give an exaggerated impression of the length. Slender free-standing marble shafts with stone bell-capitals divide the bays, with side shafts, also of marble, bearing foliage capitals. The lancets are contained in the moulded, slightly stilted centre arches. The triangular heads of the side ones are squeezed to fit beneath the vault. Triple vaulting-shafts, the centre one filleted, rise from big carved heads midway between the abaci of the piers and the clerestory, minimising what would otherwise be a strong vertical. Where the shafts cross the string-course below the clerestory are marble capitals, from which the vaulting ribs branch out, meeting at large central bosses. Parallels with Chichester and, at one remove, Canterbury choir have been seen (1 p46). The easternmost boss, which shows eight heads in a circle, displays particular affinities to carving at Chichester (Watney p25). The rere-arches of the roll-moulded east lancets have free-standing marble shafts, with rings and foliage capitals, and pointed heads with dogtooth. Carved heads flank the stilted part of the centre one. Below the sills of the lancets in the aisles is a continuous string-course and each aisle is vaulted in eight bays with plainer filleted ribs. The western octagonal piers of the arcade are smaller in diameter, so the ribs fit awkwardly onto the abaci. The vault of the second bay of the south aisle was altered when the de la Warr chantry was built.

As noted, work on the choir overlapped with the completion of the parochial nave and the alterations to the two monastic bays, though there is room for discussion about the precise sequence. The alteration of the latter, with a vault and a lancet-clerestory with marble shafts and string-courses between the heads, surely follows the choir, even if this was still incomplete. The vault springs from foliated corbels with smaller bosses and the form of rib, two roll-mouldings separated by dogtooth, is found on a smaller scale at Aldingbourne nearby and follows the south transept at Chichester. Too little of the vault of the parish nave remains to say if it was similar, but it is likely. When the parish nave was being built, the stone pulpitum, dividing the nave with two blocked round-headed doorways, probably C12, was altered. Today it is the lower part of the west wall of the roofed stump of the nave. The blocked, moulded west doorway of the south aisle is definitely C13.

Later changes to the church were relatively minor. In the choir aisles, the C14 reticulated tracery of both east windows, though renewed, looks trustworthy and two south windows are of the same period. Their heads curve inwards but are cut off by the roof and the tracery has been distorted to fit, probably as the result of an error. The final C14 addition was a chapel in the angle of south nave and transept, with a two-light quatrefoil-headed west window. In 1805 one Sharpe Collection drawing shows an outer arch, so it was already a porch, though the present arch is C19. A C14 doorway into the church looks reset – according to a tradition it comes from the nave (TP). Despite repairs, it bears a number of incised crosses and the outer order is moulded with rather mean abaci on only the inner one. The other Sharpe drawing of 1805 shows a small building east of the north aisle with what look like C14 windows, of which nothing remains

In the C15 the transepts were divided into two storeys by wooden floors, with panelled undersides with bosses at the intersections. The heads of the north and south crossing arches contain wooden traceried mullions, which look substantially old, though the Burrell Collection drawing (1781) shows solid blocking and the lower parts appear to have been restored, probably in the C19. The purpose of these is uncertain. One possibility is that they were intended simply as ceilings, but they seem needlessly elaborate for this purpose and there are no obvious instances elsewhere. However, in support of this suggestion is the lack of access to the one in the north transept and the fact that the beams are not aligned with a fireplace to be found there, though this could result from later alterations. An alternative explanation is that the floors were inserted to provide a place to say the night-time services (VCH 4 p148), for the Rule of St Benedict laid down that these should be said in the church, but not where. In winter it could have been preferable to remain in a relatively small heated area near the dorter. This does not explain the floor in the south transept, as the monks easily fitted into the north one. A doorway between the north transept and cloisters and two south windows with renewed panelled tracery, all segment-headed, are the chief external evidence of the alterations. The windows are low because of the new floor. Also C15 are a vestry north of the choir, with square-headed windows, and the large windows in the first and third bays of the aisle with panelled tracery. Access to the conventual buildings was improved by the insertion in the north wall of the surviving monastic nave of a doorway with complex mouldings beneath a squre hoodmould, now blocked, and battlements were added to the tower. The south east buttress of the choir was rebuilt in the late C15. A date is provided by one of the two shields on its small gable, which has been identified as that of Prior Richard Chase or Chese, elected in 1485 (TP).

The chantry in the choir was built by Thomas, Lord de la Warr for himself and his wife between 1530 and 1535 and led to a major internal alteration. A single four-centred arch replaced the C13 bay and the aisle vault was adapted accordingly. The chantry is more a piece of architecture than a monument in any conventional sense. Ironically, in view of his plea to Henry VIII, de la Warr was buried at Broadwater in 1554. This was probably because he fell out of favour and was compelled by the King to exchange the manor of Halnaker in Boxgrove for Wherwell in Hampshire in 1540 (6 p11) and thus had no further link with Boxgrove, whereas the manor of Offington in Broadwater remained his main seat. Added to this was the abolition of chantries in 1547, which meant that by the time of de la Warr’s death this could only have functioned as a tomb. The chantry was used as a family pew by the Dukes of Richmond in the C19 and is in remarkable condition. The plan is rectangular with two bays on the long sides, each with pairs of cusped arches separated by pendants, which are also present on the vault inside – the short ends have none. The base is essentially gothic, decorated with shields within lozenges. The upper part, especially the corner-shafts and those between the bays, is covered in Renaissance ornament of shallow incised figures and foliage, some based on Paris woodcuts of c1500 (2 p127). The canopy also combines such decoration with gothic elements – pairs of angels and putti hold shields with straight heraldic decoration. Tiered niches for statues, if ever filled, are now empty. Inside, the reredos has more empty niches, either side of a blank space intended for a carving. Each side of the reredos is an opening, of which that to the main nave of the church served as a squint. The purpose of the recess to the south was probably to provide symmetry. A small opening on the south side but lower down is too small for a piscina and its purpose is uncertain. The painted interior is mostly restored and the iron gates survive.

After the dissolution a wall beneath a half-hipped gable, as shown by Nibbs in 1851, was built on the pulpitum to separate the parish nave, which was abandoned, and a late C16 segment-headed doorway was inserted on the site of the former stairs to the monks’ dormitory, with a plain window in the upper south transept wall. Otherwise, there was little structural change until the C19, though the church was filled with box-pews (6 p11). The claim that there was a partial restoration at an unrecorded date by W White (Leeney: SAC 84 (1944-45) p132) can surely be discounted as it is not mentioned in Gill Hunter’s recent study of the architect; it may result from confusion with the building of a new vicarage (since disappeared) to White’s design in 1858 (Hunter p270). The main restoration was undoubtedly that by Sir George G Scott in 1864-65, at a cost of £4000 (B 23 p198). Scott rebuilt the flying buttresses and the west wall, as well as the west window. To a remarkable extent he retained the old patina inside and out and though much stonework is new, he kept later mediaeval changes. The form of the arcades seems to have left its mark on Scott, for it is repeated at one of his last new churches, Fulney, Lincolnshire, built between 1877 and 1880 (for an illustration see Stamp (p137)). At least two further architects have worked at Boxgrove. In 1886 L W Ridge restored the tower roof and panelled the inside (CDK 1887 part 2 p147) and in 1931 W H Godfrey restored the chapel of St Catherine (CDG Nov 1931 p458), though he never wrote about the church. In 2008-09 the whole church was closed for restoration by St Ann’s Gate Architects (notice in church) and as most floors were taken up, there may have been discoveries about the construction of the present church, as well as the form of the first choir, so publication in due course of what was found could thus be of great interest. As part of the re-flooring the remarkable labyrinth was placed under the crossing. This was designed in darker stone to a design by S van Driel (BE(W) p168).

Monastic buildings

The monastic buildings stood north of the nave and transept around the cloisters, which may have been timber, as no trace survives except the roof corbels on the outer side of the nave. The dorter (or dormitory) was north of the transept above the chapter house and other buildings. The stair into the church from the dorter may have been altered when floors were inserted in the transepts. The chapter house entry survives and was one of the first parts of the priory to be built. Its three round-headed bays of c1120 or slightly later, with squat piers and scallop-capitals, are massive to support the dorter above. The most substantial survival is the block standing to its full height to the north of the main range. This was used both as the prior’s lodging and as a guest house and the detail is of c1300, with lancets and a two-light north window with a shafted rere-arch and fragments of geometrical tracery. There was a vaulted undercroft, divided by pillars down the centre.

Fittings and monuments

Altar: The new high altar is made of stones from that in the chapel of Halnaker House and includes a consecration cross (TP)

Aumbries: (Both aisles at east end) Pointed and roll-moulded, so they are probably C13.

Bracket: (South east crossing pier) Small image bracket which is hard to date. There is provision beneath it for a candle.

Brasses: (In outer south porch) C15 or C16 square-headed niche with cresting, containing indents of brasses of kneeling, facing figures. A connection with the Selsey group of monuments is possible, recalling the type to be found, for example, in Westhampnett, the next parish.

Font: C15 octagonal, with a panelled stem and quatrefoils on the bowl.

Glass:

1. (North aisle, first and second windows) Clayton and Bell, c1898-1901 (www.stainedglassrecords.org retrieved on 4/2/2013).

2. (East window) M O’Connor in memory of the Duke of Richmond, 1862 (signed).

3. (North aisle, east window) Workshop of O’Connor, 1871 (TP).

4. (South aisle, four lancets) E S Ford, made by Lowndes and Drury (JSG 24 p52 and CCL 1920) with the personal involvement of Mary Lowndes. The single figures with heavy features are not unlike the late works of D G Rossetti.

5. (South aisle, second and fourth windows) A Gibbs, 1887 (one signed).

6. (South aisle, first window) Kempe and Co, 1916.

7. (North aisle, first window) E W Tristram, 1948 (www.stainedglassrecords.org retrieved on 4/2/2013).

8. (West window) Abstract by N Kantorowicz, 1998 (signed).

9. (South aisle, third window) Memorial window to Billy Fiske, an American pilot killed in the Battle of Britain, so both a Hurricane fighter and the US flag are depicted. M Howse, 2008 (Artist’s website)

Mass dials: (Rebuilt south east buttress of choir) Three in number and possibly not in situ (TP).

Monuments:

1. (South transept) Two C15 tomb chests of marble, the finest at the entrance is free-standing, with sides bearing quatrefoils containing shields. The other is plainer.

2. (North aisle, near east end) C15 tomb with a canopy with a very depressed head. The chest has alternating cusped circles and cinquefoiled panels, one of which has been repaired with trefoil-headed panels that do not fit.

3. (South aisle) Three tomb-chests, all looking C15:

a). All marble with small double-cusped circles on the chest

b). (Beneath second window) The chest is low with an arcaded side, and it probably had a brass on the top.

c). (Beneath third window) Set in a recess with a cusped depressed head and an ogee-label. The low chest has a band of quatrefoils.

4. (North transept) Sir William Morley, 1728. This comprises a large urn on a base.

5. (North transept) Mary, Countess of Derby (d1752), daughter of the last. There is a relief of the countess distributing alms in the parish, where she founded almshouses. Attributed to T Carter by Mrs Esdaile (BE(W) p168) though not in Roscoe.

6. (West wall) Tablet to the 8th Duke of Richmond by W A Forsyth (CDG Apr 1938 p146) and a relative killed in the Russian campaign of 1919. The painted inscription is contained in a wreath.

7. (South aisle) Admiral Nelson-Ward (d1937) by C Thomas (BE ibid). A recumbent but lifeless bronze effigy.

Niche: (South east crossing pier) Small and probably C12 or C13.

Paintings:

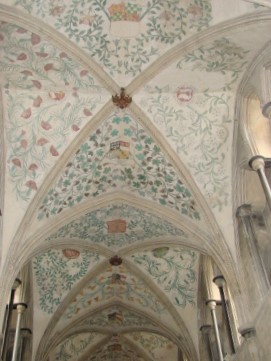

1. (Choir vault) Decorations by L Barnard for Lord de la Warr (Croft-Murray p112), probably linked with his chantry. Naturalistic foliage, interspersed with the arms of de la Warr and relatives.

2. (North west respond of choir arcade, west wall of south aisle and in south transept) Mostly decorative painting and probably C13. Parts are quite clear, particularly the figure in red on the west wall of the transept, which has been interpreted as St George (Rosewell p296). This work has been conserved by McNeilage Conservation (partnership website).

Piscinae:

1. (Exterior on west wall) Triangular headed, probably late C12. This would have been for the parish altar.

2. (East wall of north aisle) It is lacking a head and has a bowl on a shaft. It is most likely to be a C15 insertion.

3. (South aisle at east end) C13 pointed and roll-moulded.

4. South transept) C13 pillar piscina with the top formed from a volute capital.

Pulpit: Designed by Scott (BE(W) ibid).

Recesses:

1. (South aisle) Elliptical and cusped with pinnacles.

2. (North aisle) Similar, but with head stops and no pinnacles.

Reredos: Designed by Scott and carved by carved by Farmer and Brindley.

Stoup: (By south doorway) C15 or C16.

Tiles: (East end of south aisle) Collection of mediaeval tiles around altar. Some are said to be Flemish (BE(W) ibid).

Sources

1. C J P Cave: The Roof Bosses in Canterbury Cathedral, Arch 84 (1934) pp41-61.

2. : Note on the de la Warr Chantry, Arch 85 (1935) pp127-28

3. C Lynham: The Priory Church of Boxgrove, JBAA 42 (1886) pp68-75

4. R McDowall: Boxgrove Priory, AJ 142 (1985) pp64-66

5. J L Petit: The Architectural History of Boxgrove Priory, Chichester 186

6. W H St John Hope: Boxgrove Church and Monastery, SAC 43 (1900) pp158-67

7. E Turner: The Priory of Boxgrove, SAC 15 (1863) pp83-122

Plan

Measured plan by W D Peckham and others in VCH 4 opposite p141

My thanks to Mike Anton for the photograph of the reredos and to the vicar for the final two images of the interior