Mayfield – St Dunstan

The tower, lower north aisle walls and chancel remain from a big C13 church, known to have been damaged by fire in 1389. The church was rebuilt with a new south chapel and a south aisle, with a two-storey porch. Both arcades were almost certainly early C16 replacements and display some structural peculiarities, probably the result of the insertion of a roodscreen and loft.

Mayfield was one of the largest villages in the deanery of South Malling and the Archbishop of Canterbury had a palace, the remains of which are incorporated in a C19 Roman Catholic convent and school behind the church. It is probably the oldest major settlement in the area and adjacent parishes are likely to have evolved from dependent chapelries; this was certainly so in the case of Wadhurst. The significance of the proximity of the palace to the church was reinforced in the mid-C13, when the Archbishop was granted the rectory (see paper by TC). As a consequence of this link, the history of the parish, and thus of the church, in the late Middle Ages is unusually well documented. In the C16, Mayfield was a centre of Protestantism and the home of three of the ‘Lewes Martyrs’ (4 p32), though its status as part of the deanery had no bearing on this, for other parishes not under archiepiscopal control were similarly affected. Remarkably, four members of the Kirby family held the living in succession between 1780 and 1912.

The dedication to St Dunstan, archbishop from 960 to 988, could suggest a foundation soon after the saint’s lifetime (T Tatton-Brown: The City and Diocese of Canterbury in St Dunstan’s Time, p81), though no part of the church is older now than the C13. A large church, it had already reached its present dimensions by this date, for the tower and the rubble walling of the north aisle and chancel are all C13 and the south aisle, though entirely later, may have had a predecessor. A west lancet in the north aisle and the jamb of a north one in the chancel remain. The latter is set high in the wall, which could suggest that the chancel has been reduced in height. Nothing is known for certain about the form of the arcades (or arcade if there was only one), but during a recent re-ordering of the west end (see below), the octagonal base of what may have been a pier was found adjacent to and partly beneath one of the present arcade piers (it is now concealed beneath a cover in the floor) – the alternative explanation is that it is the base of a font. It would be large for this purpose (the presumed diameter would be 2.2 metres (TC)), but there are comparably sized ones in East Anglia. In favour of this interpretation is the fact that it is not in line with the bases of the present arcade (as the aisle behind was largely retained this would surely have followed the line of its predecessor); against it is the position since mediaeval fonts were more often on the south side of the church. Its position shows that if it belonged to an arcade, that would have been differently spaced, but this could be explained by the unusually long return-wall west of the arcade. The masonry of this resembles that of the rest of the later north wall and its length could have been determined by the need to provide stronger buttressing for the tower when the present arcade was built. The consultant archaeologist, (Christopher Greatorex) (see his report on the church website) considers the base to be ‘Norman’ (i e later C11 or C12), though its form does not preclude it being C13, like the other early parts of the present church. The tower is substantially C13, with angle-buttresses, side-lancets (on all three sides higher up) and a triple-chamfered doorway with thin abaci. However, there have been alterations, starting with the three-light C14 west window with cusped intersecting tracery, and a blocked double-chamfered north doorway.

The architectural history of the church during the late mediaeval period is complex and some of the questions that arise are not easy to answer. The starting date is a fire in 1389, which damaged the church and destroyed much of the village besides. It is well attested (e g 2 p17) and some of the masonry of the present church shows signs of scorching, both inside and out. The church was not entirely destroyed and within a relatively short space of time the chancel had been restored, though perhaps as a consequence its north wall leans outwards. Its side-windows, especially on the north side, have straight-sided quatrefoils in the heads and there is a big five-light east window. This has panelled tracery, which includes a large curved quatrefoil in the head of a type that can be dated to soon after 1400. The south chapel is of the same date, as the ogee-headed lights of its east window and the three-light south windows show.

The south aisle, west of the chapel, was built soon afterwards. This is most evident from the windows, though there are variations, particularly at the parapet level, where the corbels of the chapel are omitted. The aisle is twice as wide as the north one and has what appears to be the original roof, with moulded beams dividing each bay of the aisle into two parts; that of the chapel is similar but in three parts. The two-storeyed porch resembles several others of the period in the area, with a triple-chamfered arch, battlements and a polygonal stair leading to the upper chamber. It is vaulted inside with a boss carved with a dragon and ridge-ribs. The doorway has a square hoodmould and traceried spandrels.

The exterior of the north aisle shows that though the fabric and dimensions of the C13 aisle were kept, it was substantially heightened and new windows with a simpler version of the early C15 panelled tracery were inserted. The new masonry is of squared blocks, which can immediately be differentiated from the C13 rubble. As a consequence of the heightening, the aisle has an almost flat roof, though the present one is later. The final identifiable changes during the immediate post-fire period were to the tower. This was heightened, with uncusped square-headed double bell-openings and, probably the broach-spire, which recalls that at Wadhurst, also in Malling deanery, though that is steeper. On the east side of the tower, immediately above the apex of the present roof is what appears to be the hoodmould of a further square-headed opening, also probably of two lights.

Uncertainty starts when examining the nave arcades. These have octagonal piers on strikingly high bases and four-centred heads with two hollow chamfers. There are five bays, but the easternmost ones to the eye appear to consist of only half an arch and there are no east responds. This has led earlier writers to speak of an arcade of four and a half bays (e g BE p565), but it has been established that the final arch is of the same width as all the others except the north west one (TC). Comparable arrangements exist in Kentish churches (TC). Fairly close by at Goudhurst, Kent, earlier arcades were altered in a similar way during the ‘Perp’ period, and slightly further afield the same happened at Biddenden and Woodchurch. At the last there is a record of a bequest for a new roodloft in 1515 and at Goudhurst the changes have specifically been linked to the insertion of a roodscreen and loft (BE West Kent and the Weald (2012 edition) p257). There can be little doubt that similar considerations applied at Mayfield. This is all the more likely because the easternmost clerestory windows have three lights instead of two, which would have provided more light to the loft.

The clerestory windows are four-centred and there is every sign that the upper parts of the nave are of the same build as the arcades. This suggests that the nave in its present form dates from the early C16. The evidence that there was a rood shows that this cannot have been post-Reformation work, as Godfrey suggested tentatively, citing a record of lightning damage in March 1621/22 (4 p180).

Assuming most of the nave dates from the early C16, the question arises of what happened to it after the fire of 1389. It is unlikely that it stood open to the weather for over a century, in view of the building of the new south aisle and the alterations to the north one. It is also improbable that the parishioners, responsible for the upkeep of the nave, would have been so negligent in their duty, even if because of the immediate need to rebuild their houses, they responded more slowly than the archbishop who, as rector, was responsible for the chancel. The likeliest answer is that the previous arcades were kept and replaced a century later, possibly because they proved to have been weakened by the fire. The fact that the south arcade is similar to the north one suggests strongly that there was in fact a south aisle before the fire, for if there had not, a south arcade would have had to be built afterwards to give access and this would hardly have been rebuilt after only a century.

There is documentary evidence that there was a new rood in the early C16 (TC) and it is likely that the rebuilding of the nave along the lines noted above took place at the same time. Probably when the new screen and loft were installed, the chancel arch, presumably the one that had been there since the C13, the date of the fabric of the present chancel, was removed. The chief evidence for this is to be seen in what would have been its south respond, which has been awkwardly cut away. As with the missing east responds of the arcades, any such awkwardness would have been unimportant, since the screen and loft would have concealed it, at least on the south side, where it would have been quite usual for the loft to extend across the arch to the south chapel, ending perhaps a little before the window in the south wall of the aisle so as not to block it. Matters are complicated by the adjacent two-bay arcade from the chancel to the south chapel. This is closely related to the nave arcades and can be assigned to the same period. Presumably the post-fire alterations had not included any arcade in this position, though there could have been a small opening. Such a chapel was probably a private chantry so nothing more would have been needed; there are a number of instances of such an arrangement elsewhere. The need for better communication between the chapel and the chancel may have arisen as a consequence of the building of the rood screen and loft (TC) as these would have impeded access from the aisle, particularly as the presence of a piscina here (see below) indicates there was in addition an altar at floor-level.

The rood loft and rood probably disappeared in the mid-C16, as was required. The next change to the fabric must have followed the lightning damage of 1621/22. According to a contemporary description (ESRO Par 422/1/1/1 f92 – see CW’s report for a transcript) the south aisle was seriously damaged at both east and west ends and the tower and chancel were also affected. It is likely that the previous west window of the aisle dated also from this period. It is shown best by Saunders (p65), shortly before it was removed. It had a square head and was divided both by mullions and a transom, making it unlike any earlier window in the church. During this period the aisle was in use as a school (Langdon p65).

The church was re-roofed in accordance with the will of John Baker, which is dated 1716, though he did not die until 1725 and had previously donated the timber in 1720 (CW). Until the roofs were replaced again in 1869, an inscription on the nave roof recorded the gift (5 p360). The plain roof of the north aisle, which is quite unlike that of the C15 south aisle or the C19 ones elsewhere may be all that remains of this work.

As happened with many churches during the post-Reformation period, the tower arch has been blocked with masonry in which a small possibly late C13 or C14 doorway has been reset. This is plain and if genuine, probably comes from the archbishop’s palace, as may the rest of the masonry. Generally, blocking of this kind was associated with the building of a west gallery and one is recorded in 1732 (CW) whilst there was certainly one in 1840. Victorian restorers disliked such blocking and it is unusual to find it has survived, even if the gallery has not.

W Slater and R H Carpenter at the restoration in 1867-69 (ICBS) put shiny pitch pine roofs on the nave and chancel, as well as replacing the west window of the south aisle, which is the only significant change since the Sharpe Collection drawing (1803). They restored the rest of the stonework on the lines of what was found. C E Powell further restored one window in 1899 when new glass was installed (CDG 66 p73) and there were repairs to the exterior by R Wood in 1976-77 (ICBS). The centre light of the east window was damaged in the hurricane of 1987 (CBg 13 p30), though there is no obvious sign of this, and the Lady Chapel was damaged by fire around 1998. In 2007-08 the west end was re-ordered by J D Clarke and Partners (church website). Work included the removal of the top of the blocking of the tower arch and its replacement by glazing. This confirms that the blocking is not structurally necessary.

Fittings and monuments

Altar: (Lady chapel) R Wood, 2001-02 (1 p22).

Altar rails: C18 with turned balusters.

Aumbries:

1. (South chapel, south wall) Plain square-headed, probably C15.

2 (North aise, east wall) Small and plain and impossible to date.

Bench ends: Two C16 ones with poppy-heads.

Candelabra: (Nave) Fine brass, dating from 1737 and 1773.

Commandments etc: (East wall) These have rounded tops and date from c1750 (1 p14).

Font: Octagonal bowl dated 1666, with the initials of the churchwardens and various patterns in shallow relief. Drummond-Roberts (p59) called it C15 in origin, but this can apply at most to the arcaded stem.

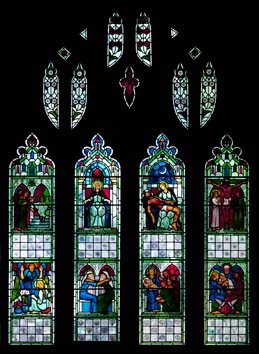

Glass:

1. (East window) Mayer and Co, 1869 (BN 17 p156). It was replaced in 1907 at half price because it had deteriorated (4 p77). It had done so again before storm damage in 1987 led to further restoration.

2. (One south chancel window, two north chancel windows and five in the north aisle, including the west and east windows) Mayer and Co, 1872-1906 (www.stainedglassrecords.org retrieved on 17/3/2013).

3. (South aisle, third window) C Webb, 1950 (DSGW 1952).

4. (South aisle, west window) F W Cole, 1993 (signed).

5. (South Chapel east window) M Lawrence, 1999 (JSG 23 p88).

Monuments:

1. (South aisle) Thomas Anscombe (d1620) and his wife (d1633). He and his wife kneel facing, above their family. The figures are contained within an arched surround, on each side of which is an angel.

2. (Nave floor) Two iron tomb-slabs, dated 1668 and 1708. Both commemorate men called Thomas Sands (who were grandfather and grandson). The earlier one is of unsophisticated workmanship with reversed letters and figures, but the later one shows the family arms as well as the customary inscription.

3. (South chancel floor) John Baker (d1669) Iron tomb-slab (see under 4. below).

4. (Chancel floor) During alterations to the chancel in 2014 four further iron tomb-slabs were uncovered, in addition to that of John Baker (see 3 above), though details had previously been recorded on the wall. The slab to John Baker has his arms and an inscription in Latin and the second, dated 1671, to Dorothea Baker, his widow, is very similar. The other three are undated, quite plain except for the initials of the departed. They commemorate Thomas Houghton (d1666) and his wife (d1669) and son (d1671) (Information from TC)

5. In addition, two badly damaged and as yet undated slabs, thought to be of Sussex marble were found. One at least is thought to be associated with the monument to Thomas Anscombe (see 1 above) which was in the chancel until the C19 (ibid).

6. (South chapel) George and Philadelphia Baker by S Oliver (Roscoe p925), erected in 1765. Llewellyn (p233) provides the actual dates of death, 1756 and 1741 respectively.

7. (North chancel) Michael Baker (d1750) and wife (d1796) by C Regnart (ibid p1028). In view of Regnart’s dates and the late C18 style (a sorrowing woman leaning on an urn), this must have been erected after the death of the wife.

8. (North west nave) Philadelphia Godfrey (d1807) White marble, signed Browne and Co, London.

9. (South aisle) Richard Owen Stone (1824?) by L Parsons (ibid p952).

10. (South aisle) Members of the Treherne family (after 1953). Tablet with lettering by J Skelton (1 p12).

11. (Over entrance to chancel from nave) ‘Resurrection Spirit’ by M Hambling. A silver dove-like bird in memory of Walter Podger (d2008), which was dedicated in 2013.

12. (South nave) Apsley Philip Treherne (d1922) and Georgina Weldon (d1914), Inscription set in a pedimented frame and more elaborate than most of his memorials by E Gill, 1922 (E R Gill p61).

13. (Churchyard) There are no less than 11 tombs given to J Harmer, the latest of which is dated 1811.

Piscinae:

1. (Chancel) Square-headed with a shelf, probably C15.

2. (South aisle) Larger with a cusped ogee head. It too is probably C15, though the form could be C14, in which case it must be reset.

Pulpit: Cut down early C17, with shallow arabesques carved on the sides.

Royal Arms: (Formerly over tower doorway and now in the north aisle). Painted; George I.

Screens:

1. The otherwise C19 west return of the choir stalls incorporates early C16 linenfold panels in the base, quite possibly from the roodscreen, as the date would fit. These have clearly been moved.

2. (Parclose round south chapel) F Rosier, 1923 (1 p14).

Squint: From south chapel to chancel.

Statue: (North nave) Virgin and Child by G Webb (after 1943) (1 p13).

Sundial: (South porch) Probably C16 or later.

Sources

1. J Barnes: A Guide to the Church of St Dunstan Mayfield, 2003

2. W D Cooper: Mayfield, SAC 21(1869) pp1-19

3. E H W Dunkin: History of the Deanery of South Malling, VIII – Mayfield, SAC 26 (1875) pp59-71

4. R C G Foster: Mayfield, a History, Mayfield, nd [1960s]

5. W H Godfrey: St Dunstan, Mayfield, SNQ 6 (May 1937) pp178-80

6. E Roberts: On Mayfield in Sussex, JBAA 23 (1868) pp333-69

Plan

Measured plan by W H Godfrey in 3 p179

Acknowledgements

1. Particular thanks are due to Tim Cornish (TC), who has made available his paper on the origins of Mayfield and also an unpublished report of 2007 by Christopher Whittick (CW) which examines the evidence, mainly documentary, for the work done on the church in the C17 and C18. TC has also shown me round the church, in particular the most recent finds, and has undertaken research into the question of the changes made in connection with the presumed roodscreen and loft. However, in fairness to him, I must make it clear that he is not responsible for any of the conclusions above.

2. Many of the colour photographs above have been taken by Nick Wiseman. My grateful thanks to him for making them available.

3. I am also grateful to Mike Anton for the photographs of the Anscombe monument, both Sands tombslabs and the candelabrum.