Upper Beeding – St Peter

The oldest part dates probably from the C12, but it has been extensively altered twice, first probably in the mid-C16, when the chancel and upper tower were rebuilt incorporating some C13 and C14 work, possibly from the priory that used the church and again in 1852, the date of the south aisle.

The bridge and causeway at Upper Beeding belong to the main mediaeval east-west route through Sussex. It was thus a place of some importance and Domesday Book lists two churches (13, 1). The other might be thought to be Botolphs but that is listed separately as Annington, with specific mention of a church. More likely there was some kind of church or chapelry in the Wealden outlyer, known confusingly as Lower Beeding, though it disappeared subsequently since the present church there was only re-established in the C19.

After 1075 the parish church of Upper Beeding was shared with the adjacent Sele Priory, founded by William de Braose, Lord of Bramber, as a daughter house of the French abbey of Saumur. Though the link with Saumur went in 1396, it was dissolved because of corruption in 1459 to help endow Magdalen College, Oxford, which held the advowson until the 1950s. In 1493 its monastic buildings are said to have been leased to the Carmelite Friars of Shoreham, whose house was threatened by the sea (Lower I p45). These buildings were north of the church and the former vicarage now stands on the site. Entirely rebuilt in 1790 (2 p103), it is now called the Priory. Excavations in 1966 revealed what may have been foundations of a cloister north of the chancel (MA 9 (1966) p276). After the friary was in turn dissolved in 1538 (VCH 2 p97), the church became exclusively parochial.

This historical background is important to understand the development of the church, which is anything but straightforward. It has been assumed that the earliest part is the north wall of the nave, together possibly with the lower stage of the unbuttressed tower; nothing is now visible of a two-light round-headed bell-opening described by the young Sir Stephen Glynne (1825?) (SRS 101 p292) which if reliable, would point to a C12 date. There is no other detail and there are no mediaeval windows in the north wall, probably because it abutted onto the monastic buildings. This wall is difficult to access as it is close to the boundary of the churchyard, but it has been generally been thought to be older than a blocked two-bay south arcade with round-headed arches shown on the Sharpe Collection drawing (1802) and by Glynne which looks C12; its existence is confirmed by Dallaway (II(2) p220) though no date for its removal is known. However, the rubble construction of the north wall on closer examination proves to contain much obviously re-used masonry that includes quite a few carved and shaped stones. It seems unlikely that this wall in its present state is C12 as has been assumed, but it is best considered further in conjunction with the chancel which shows even more anomalies. Thus the most certain survival from the church of the monastic period is the lower stage of the tower. It is visibly off-centre to the north, suggesting the nave has been widened on the south side; if so, this must have been done before the C12 arcade was inserted. Elements of the tower arch with polygonal responds and a moulded and pointed head appear little later, but the distortion of the voussoirs indicates some alteration, always assuming that it is in situ.

Unquestionably later mediaeval work is sparse, though the main timbers of the nave roof may be C14 or C15. A four-centred recess in the north wall of the nave looks to be of this date and could be connected with the north doorway shown on a plan of 1852 (ICBS). During this period, the chancel is said by the VCH (6(2) p44) on the evidence of an entry in the Sele Chartulary) to have been reconstructed in c1308 with north and south chapels. Nothing of this survives for the present one is too short to have been a monastic one, since these are long, as those at Lyminster and elsewhere show.

The present chancel raises in even more emphatic terms the same questions as the north wall of the nave. It too is largely built of re-used masonry, which has been treated in a variety of ways. In the upper part of the east wall one worked fragment displays chevrons and is thus mid-C12. In the south and east walls there is much use of carefully shaped ashlar which to the south is contrasted with squares of flintwork to create a chequerwork effect. This must have been intended to be seen, though the use of randomly placed rubble to level up the walling where needed might seem to contradict this. Assuming that at any rate most walling was intended to be visible, some explanation is needed of the marks in the stonework, particularly the small holes (surely too many to have been intended for mass-dials, of which there is no other trace) and peck-marks of the kind sometimes intended to improve the adhesion of render. It seems unlikely that any render was intended, assuming the ashlar was there for a purpose, so the marks most probably result from everyday wear and tear.

Further complications in the south wall are a reset round-headed doorway and two conjoined small round-headed openings with the springing of a third. These show workmanship of a high order, with deep mouldings and tiny clustered shafts and were commented upon by Glynne. Today they serve as windows but they have also been seen as arcading (NFSHCT Newsletter 2013 p5), possibly belonging to a cloister. The third fragmentary opening shows what may be signs of having been trefoiled, though this has been questioned (by Robin Milner-Gulland in a personal communication). If so, that could suggest the whole structure of three or more openings was originally late C13 though there must be some doubt about such an obviously reset feature. Round heads would not necessarily contradict a C13 dating, for round heads of the period do exist, e g at West Wittering, though the voussoirs here are slightly distorted and this could also be interpreted as showing they belonged originally to pointed openings.

An indication of the possible date of such an alteration is provided by the four-centred southern rere-arch which looks C16 and could suggest that the chancel was rebuilt shorter and more simply after the dissolution of the priory. Sometimes dating may be assisted by the roof-timbers, but here they are too plain to be of help, though they look older than the C19. The redundant priory can reasonably be seen as the source of the building material needed, some if it of high quality, but a rebuilding at this time would have had to have been quite soon after 1538 since the rere-arch of the doorway is visible inside and shows it was a functioning one. Such doorways lost much of their purpose after the further liturgical reforms of the mid-C16. One final unsolved puzzle in the chancel is the presence inside of what looks like an eastern quoin, about 1 to 2 feet from the present east wall. It seems unlikely that a later extension would ever have been so short, though the east window dates from 1852 and shows that there were alterations then so it cannot be ruled out completely.

There remains the question of the north nave wall. It is difficult to differentiate it from the work on the chancel. It seems most likely that the removal or reconstruction of the priory buildings after 1538 made it necessary to strengthen the adjacent nave wall, as well as providing the necessary material.

Disregarding the questions raised by Glynne’s possible double bell-opening, the upper part of the tower has much in common with the presumed C16 post-dissolution work and is more likely to date from then, though a date of c1300 has been proposed for reasons unstated (BE(W) p673). However, it is very plain, which makes hard to be certain, though it shares the use of chequerwork, here of rather better quality, and the plain openings vary considerably, suggesting they were taken from elsewhere. The low pyramid, already shown on the Sharpe drawing, is probably contemporary with the rest of the upper stage.

By the C19, the church had become inconvenient and J Butler drastically remodelled it in 1852 (ICBS), with a gabled south aisle, arcade and traceried windows. The arcade is of some pretension, like the new chancel arch, which has mouldings and foliage corbels. Butler’s replacement east window has conventional Decorated tracery and it is probable that the single and paired lancets in the north wall of the nave are by him also. Adjacent to the westernmost of these outside is the outline of part of a window in brick which is probably C17 or C18. It does not, however, seem likely that Butler in any way responsible for the appearance of the south side of the chancel as has been suggested (1 p64) for by the 1850s he had a developed feeling for the gothic resulting from his association with R C Carpenter.

The main later change was a new parapet with brick dressings, placed on the tower in the C20 (information from the former vicar).

Fittings

Carvings:

[NB. neither can now (2016) be located]

1. (In window splay by pulpit) Foliated capital, which looks C13.

2. (By pulpit) Battered representation of an animal of indeterminate age and nature.

Font: Unusually shallow plain octagonal bowl. It could either be C14 or C15 work that has been cut down or C17.

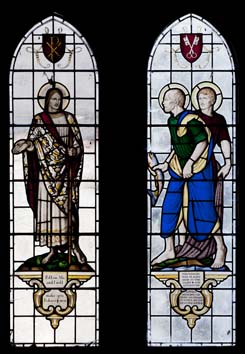

Glass:

1. (South aisle, second window and west window) W Pape of Leeds, c1909 (DSGW 1930). That in the aisle is old fashioned for its date but the west one is now entirely concealed by the organ.

2. (North nave, third window) Barton, Kinder and Alderson, 1952 (signed). This comprises figures set in clear glass.

Monument: (Churchyard) Mary Scandefeild (d1711) a tombstone with naively carved emblems of mortality, spades, a skull and an hourglass.

Reredoses:

1. There is no sign of a reredos depicting the Last Supper by J Powell and Sons of 1883, which is stated (Hadley list) to have been ordered for the church.

2. (South aisle) A three part abstract painting by M Nethercoat Bryant (Adjacent notice). It was painted in the late 1970s but only placed in the church in 2013 (Shoreham Herald 17 September 2013).

Screen: A carved fragment may come from a screen recorded in 1830 (VCH ibid).

Sources

1. H C Evans: Beeding Church, SCM 5 (Jan 1931) pp64-66

2. E Turner: Sele Priory, SAC 10 (1858) pp100-28

My thanks to Nick Wiseman for the photographs captioned NW